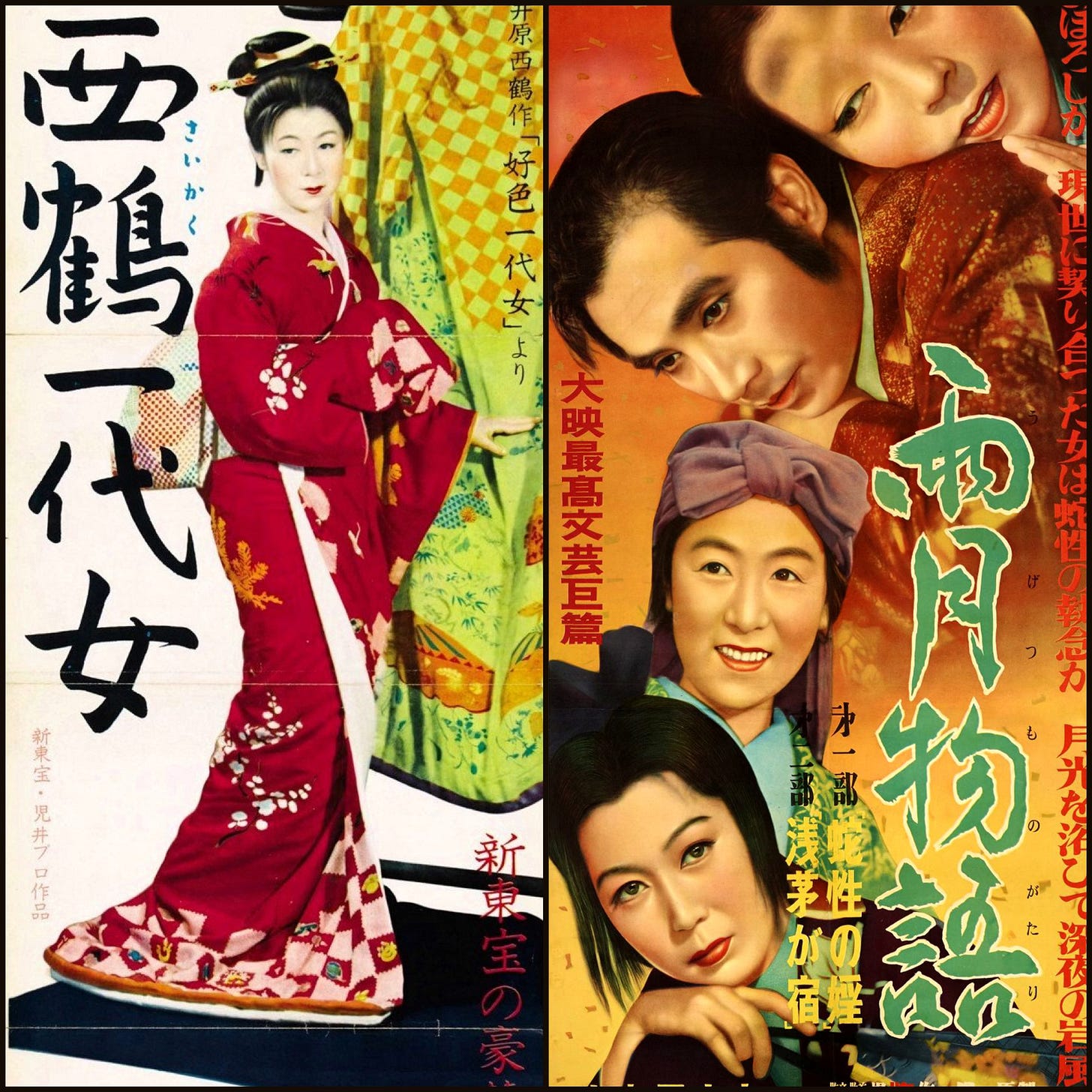

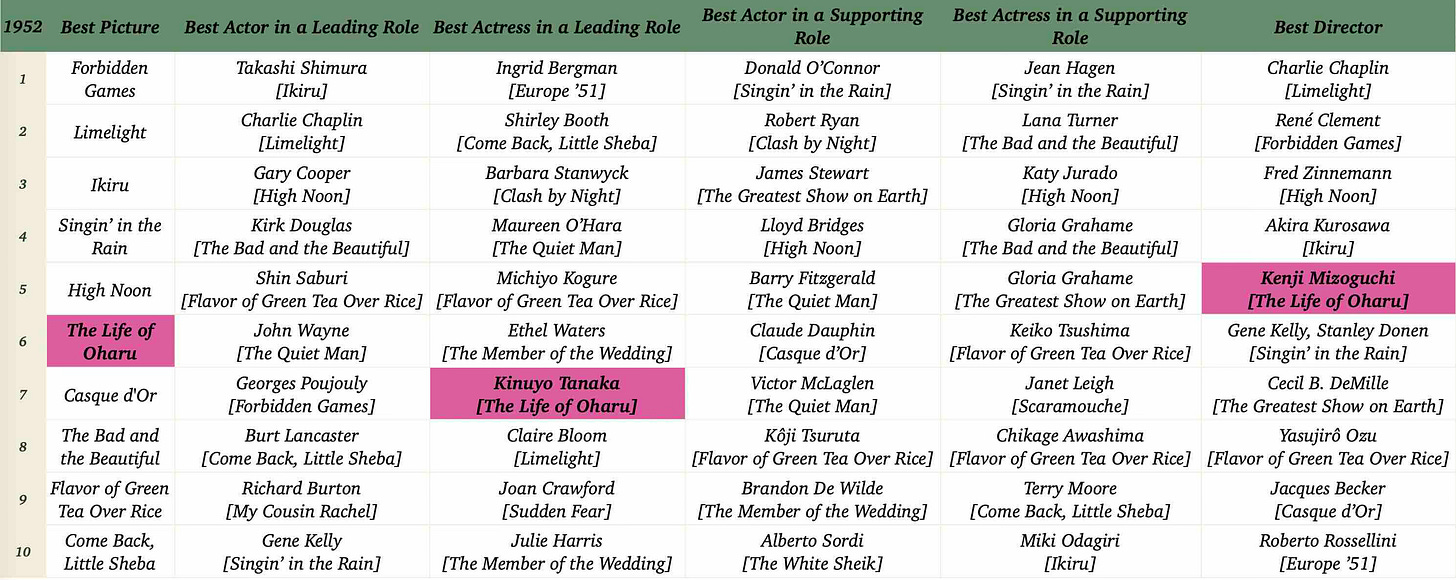

Two canonical films from Japanese cardinal aesthete Kenji Mizoguchi, THE LIFE OF OHARU is an Edo period (1603-1868) melodrama about the titular woman Oharu (Tanaka), daughter of a samurai. After a class-breaching romance with a low rank retainer Katsunosuke (a nearly unrecognizable, beardless Mifune), which finishes up with her family's exile from the court and her beau's execution, Oharu comes in for the slings and arrows, like a flowing weed, having no agency to control her own fate.

Cherry-picked as a concubine for a local Lord, Oharu is unceremoniously dismissed after giving birth to and forcibly separating from a son for heirdom (jealousy from the Lord’s wife is the mainspring), much to her money-grubbing father's (Sugai) dismay. Sold to be a courtesan, Oharu impresses a splashing-out customer (Yanagi) with her integrity, who is well-disposed to buy her freedom but only to be revealed as a fraud. This disreputable spell in the demimonde catches up with her when she is employed as a lady's maid in a well-off family. Oharu must fend off both a licentious patriarch (an oleaginous Shindô) and the ire of her prudish mistress (Sawamura). Here, a rare occurrence by her own volition reveals Oharu's cunning in retaliation by training a cat to reveal her mistress's concealed baldness.

Marital bliss is fleeting after Oharu ties the knot with a decent fan maker (Uno), who is soon killed in a robbery (still clutching tight the fine fabric he purchases for her); her entrance to nun-hood is dashed after being raped by a lewd acquaintance and another nimble-fingered one, albeit being enamored of her, is not really a man worth of her virtues. Eventually, reaching middle age, Oharu scrapes by as a street walker, numbed by humiliation and disillusion. When the tidings of her son's accession as the new Lord is relayed by her mother (Matsuura), does Oharu's ship finally come in? Mizoguchi's pensive meditation on a decent woman's repression and stigmatization offers no storybook relief. Rejected by her own son for her ill repute (which is foisted upon on her by the society at large), Oharu retains a strong will to live against the odds, which reflects Mizoguchi's very Japanese belief in "the vitality of flowing weeds". It is fairly crucial that Oharu isn't just piteously pegging out after all the trials and tribulations, yes, she is reduced to a mere mendicant, but the defiance in her eyes speaks volumes in the film's final shot.

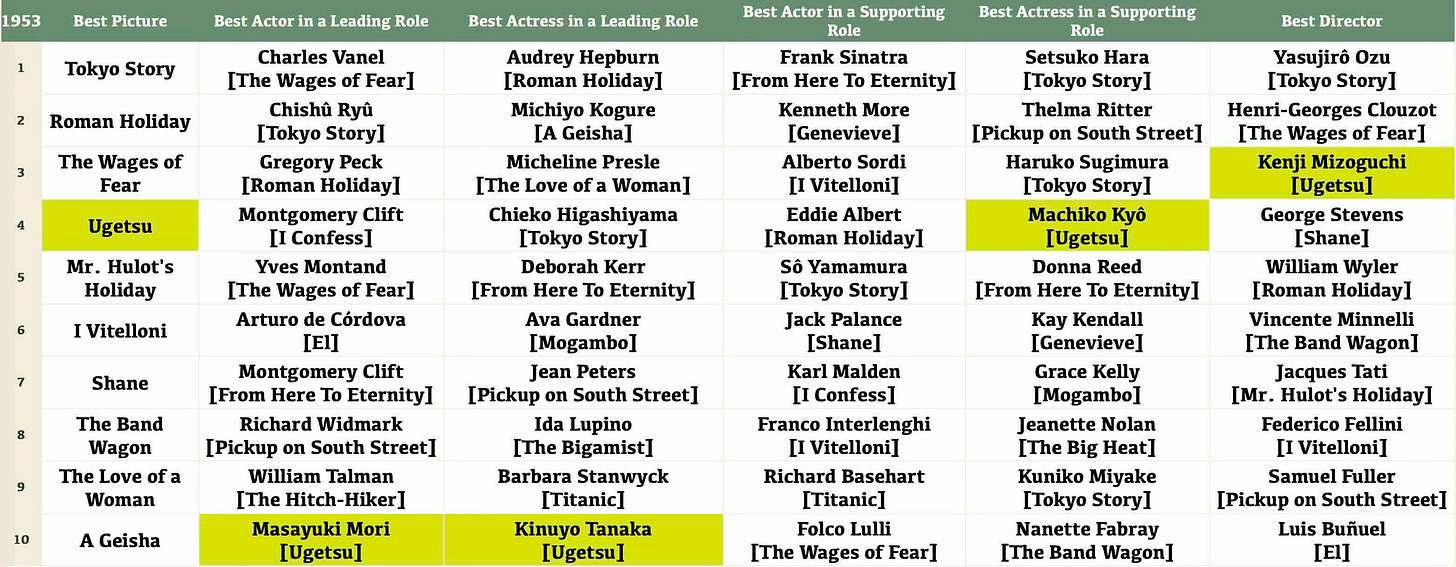

UGETSU is loosely based on two short stories of Ueda’s 1776 book of supernatural tales UGETSU MONOGATARI. The chief plot is a Sengoku period (1467-1615) ghost story about Genjurô (Mori), a skillful pot maker seduced by a beauteous wraith Lady Wakasa (Kyô), leaving his wife Miyagi (Tanaka) and their young son behind in his war-torn hometown. Bewitched under Lady Wakasa’s irresistibly alluring spell, Genjurô is only rescued thanks to a passing seer who sees the premonition of his impending doom. While narrowly escaping from the pestilent honey trap, at home, he has another ghost awaits him, to finally put him on his mettle and not tempted by the pursuance of earthly pleasures and lucres.

Ergo, UGETSU has a limpid moral message to deliver - also borne out by the byplay of Tôbei (Ozawa), Genjurô's samurai-crazed brother-in-law, whose duplicitous ascendancy is tragically at the expense of his wife Ohama's (Mito) misery - that is to reflect the untold tolls on women during the war times. Men might seize the chance to acquire gainful profits, it is the fair sex's suffering that cannot be recuperated, even Lady Wakasa is a brutal casualty of the warfare, a young woman dies before she can experience love. Together with THE LIFE OF OHARU - which elegantly and painstakingly lambastes the detrimental effects of a world-view groaning with deep-dish jaundiced values like paternalism, male chauvinism, sexism, misogyny and classism, on an ordinary woman - UGETSU establishes Mizoguchi as an inspiring proto-feminist filmmaker in the Far East, whose humane yet prudent concepts and portrayals of life's vicissitudes are granted, the finest of his time and among his peers.

In the acting front, THE LIFE OF OHARU has an innate defect in casting a 40-something Tanaka to play a girl less half of her age, which is blatantly unconvincing albeit Mizoguchi's tactful maneuvers to hide her face and largely keep Oharu to herself as much as he can. But as Oharu ages, Tanaka's soul-stirring performance comes to the fore like a smoldering heartburn, poignantly registering a woman's most relatable emotions. In UGETSU, Tanaka avails herself a more open-faced alacrity to convey Miyagi’s good nature and dutiful personality, and Mori proves himself to be a rough diamond with enough integrity to spare. However, it is Kyô’s Lady Wakasa keeps audience rapt with her Noh-opera gait and comportment, her“hikimayu”(pulling eyebrows) delicacy and period-specific finery. At once an overt no-nonsense temptress and an etiquette-versed noble woman, two faces of the mystique of a Japanese woman, regardless of eras.

Over and above the unified work of the dramatis personae, one must also marvel at Mizoguchi’s trademark techniques: gracefully mobile long takes, his divine perception of compositions and blockings, innovative effects (like double exposure and in particular, near the coda of UGETSU, when Mori finally returns to his digs, a swirling long take of the empty space contributes to an alchemical transition with a ghostlike Miyagi’s unexpected appearance, it must be bracketed as one of the most striking shots in the film history!). All events unfold like a scroll rolling (in the maestro’s own words) and such an achievement is the fruit of a collective of professions. For editing, there is remarkable economy in Mizoguchi’s narrative threads and each shot (whether long or short) is dexterously cut right after accomplishing its plot-thrusting mission. Music is also an unmissable treat in Mizoguchi’s works (Ichirô Saitô is a contributor in both film), often indigenous, pathos-ridden and phantasmically haunting. Personally, for Yours Truly, it constitutes a wondrous feeling to finally submit myself to Mizoguchi’s mastery after a bumpy start totally on account of my own callowness.

referential entries: Mizoguchi’s A GEISHA (1953, 7.6/10), THE STORY OF THE LAST CHRYSANTHEMUMS (1939, 6.3/10); Masaki Kobayashi’s HARAKIRI (1962, 8.5/10); Hiroshi Teshigahara’s THE FACE OF ANOTHER (1966, 7.8/10); Keisuke Kinoshita’s THE BALLAD OF NARAYAMA (1958, 8.1/10).

English Title: The Life of Oharu

Original Title: Saikaku ichidai onna

Year: 1952

Genre: Drama

Country: Japan

Language: Japanese

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Screenwriters: Kenji Mizoguchi, Yoshikata Yoda

based on the novel by Saikaku Ihara

Music: Ichirô Saitô

Cinematography: Yoshimo Hirano

Editor: Toshio Gotô

Cast:

Kinuyo Tanaka

Ichirô Sugai

Tsukie Matsuura

Toshiro Mifune

Eitarô Shindô

Sadako Sawamura

Akira Ôizumi

Toshiaki Konoe

Eijirô Yanagi

Hisako Yamane

Jûkichi Uno

Daisuke Katô

Toranosuke Ogawa

Masao Mishima

Eijirô Yanagi

Rating: 8.0/10

English Title: Ugetsu

Original Title: Ugetsu monogatari

Year: 1953

Genre: Drama, War, Fantasy

Country: Japan

Language: Japanese

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Screenwriters: Matsutarô Kawaguchi, Yoshikata Yoda

based on the stories by Akinari Ueda

Music: Fumio Hayasaka, Tamekichi Mochizuki, Ichirô Saitô

Cinematography: Kazuo Miyagawa

Editor: Mitsuzô Miyata

Cast:

Masayuki Mori

Kinuyo Tanaka

Machiko Kyô

Eitarô Ozawa

Mitsuko Mito

Kikue Môri

Sugisaku Aoyama

Ryôsuke Kagawa

Kichijirô Ueda

Rating: 8.5/10